West Midlands Key Health Data 2008/09

CHAPTER NINE: SURVEILLANCE OF CLOSTRIDIUM DIFFICILE INFECTION IN THE WEST MIDLANDS

Shakeel Suleman: Health Protection Agency - West Midlands

Main Body

7: Changes in Heart Attack Admissions since the Smoking Ban

8: Measuring Disability Across the West Midlands

9: Surveillance of Clostridium Difficile in the West Midlands

9.1 Introduction

Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) is the most important cause of hospital-acquired diarrhoea1. Over 80% of reported CDIs affect those aged over 65 years. The symptoms of CDI vary according to the severity of the infection, but can, in addition to diarrhoea, include abdominal pain, fever and loss of appetite. In severe cases the condition can lead to pseudomembraneous colitis (inflammation of part of the large bowel) and death 1.Various risk factors have been shown to be associated with CDI and these include:

- Age >60 years

- Antibiotic therapy

- Current immunosuppressive therapy

- Severe underlying illness

- Prolonged hospital stay

- Recent surgery

- Nursing home residence

- Sharing a room and/ or facilities with a patient who has tested positive for CDI

- Use of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs)

9.2 Surveillance

Mandatory reporting of CDI for the 65+ age group was introduced in January 2004 and was extended to all ages over 2 from April 2007. Reporting is done via the web-based HCAI Data Capture System, which is managed on behalf of the Department of Health by the Health Protection Agency (HPA). This chapter will describe the change in the incidence of CDI in the West Midlands between 2008 and 2009 and will also include a health economy view of CDI in the region. The West Midlands region consists of 19 Acute Trusts and 17 Primary Care Trusts (PCTs).

In the reporting of CDI, a distinction is made between those cases that are deemed to have originated within an acute trust and those which are not. The relevant definitions are:

- ‘Trust apportioned’ – this is where the specimen is taken on or after the third day of admission (commonly referred to as ‘post-48 hour’ cases), where the day of admission is construed as day 1.

- ‘Non-acute trust apportioned’ – any specimens taken within 3 days (i.e. on day 1, 2 or 3), or where the patient is not admitted or where the specimen is taken from healthcare settings other than an acute trust, such as GP surgeries and PCT hospitals are often referred to as community cases. Such cases are presumed to be of community origin, but in the absence of root cause analysis, however, it is difficult to determine the origin of an infection.

All post-48 hour cases are apportioned to an acute trust and count towards the trust’s national and locally agreed trajectory. All cases, whether post-48 hour or non-acute trust apportioned, are allocated to PCTs and again there are national and local targets in place.

9.3 West Midlands Regional Overview

Figure 9.1 shows the number of reports of CDI, made via the mandatory reporting system and via laboratory reporting, since April 2007, when mandatory reporting was extended to those aged 2-64. As the figure illustrates, there has been a sharp fall in the number of cases reported every month, which is likely to be a reflection of the impact of control measures implemented nationally.

Figure 9.1: Number of reports of CDI made since April 2007 in the West Midlands

|

In 2009, a total 3,176 cases of CDI were reported across the West Midlands region on the mandatory reporting system. This includes all cases attributed to acute trusts and to the community (i.e. non-trust apportioned cases). This represents a reduction of 33.6% compared with the 4,784 cases reported in 2008.

Within this overall reduction, the per cent apportioned to non acute settings increased from 44% (n=2,135/4,784) to 49% (n=1,570/3,176) in 2009 (Figure 9.2). However, as Figures 9.3a and 9.3b illustrate, at the PCT level, there was more variation in the proportional distribution of cases between acute trusts and community settings in 2008 compared with 2009, and, in several PCTs, a greater proportion of cases were not attributed to an acute trust. The observed decline in CDI incidence in the region may be attributed to improvements in surveillance and increased adherence to recommended infection control measures, the routine application of learning from root cause analyses of CDI mortality (a minimum of all deaths with CDI mentioned in part 1a of the death certificate) and improved clinical management of patients with CDI. Health economies are also now working together to improve the management of individuals in community (non acute) settings with CDI or individuals identified as having a higher risk of infection in a bid to further improve the quality and safety of patient care and improve patient outcomes.

Figure 9.2: Distribution of CDI cases between acute trust and non acute trust (community onset) in the West Midlands

|

Figure 9.3a: Proportion of cases of CDI that are not apportioned to an acute trust 2008 by West Midlands Primary Care Trust

|

Figure 9.3b: Proportion of cases of CDI that are not apportioned to an acute trust 2009 by West Midlands Primary Care Trust

|

The reduction of CDIs is subject to national targets, which require a 30% reduction in 2010/2011 against a 2007/08 baseline. However, nationally this target was met two years ahead of schedule. In the West Midlands, 7,074 cases of CDI were reported on the mandatory reporting system in 2007/2008, against 4089 in 2008/09, marking a 42% reduction. The national rate of reduction over the same period was 36%.

For 2010/2011, the CDI objective challenges trusts to make further improvements and also encourages the development of multidisciplinary, health economy-based strategies to improve on the performance in previous years. In addition to national objectives, more stringent locally agreed objectives are also in place.

9.4 Patient Demographics

Most hospital inpatients (whether pre or post 3 days) who tested positive for CDI were admitted from home, followed by those admitted from all care homes (Figure 9.4).

Figure 9.4: Location West Midlands inpatients with CDI were admitted from

|

As over 60% of patients are over the age of 75, it is not surprising that nursing homes are the second largest location from which inpatients were admitted. As Figure 9.5 illustrates, CDI primarily affects older people, with 80% of patients aged 65 years and over.

Figure 9.5: Age distribution of CDI patients, West Midlands, 2008 – 2009.

|

Maps 9.1a and 9.1b show the rate of CDI in PCTs in the region (includes acute trust and community cases) by background Indices of Deprivation in 2008 and 2009. There does not appear to be any correlation between deprivation and the occurrence of CDI, however, it is apparent that there has been a clear reduction in CDI rates in most PCT areas between 2008 and 2009.

Maps 9.1a and 9.1b: Rates of CDI per 100,000 of West Midlands PCT population mapped against Indices of Deprivation. All positive CDIs reported on the HCAI Data Capture System for the relevant periods have been used for these calculations.

9.5 Link with Norovirus

Noroviruses are a leading cause of acute viral gastroenteritis, particularly in the winter months. Symptoms generally include vomiting and diarrhoea, but can also include fever and abdominal cramps.

There is no causal link between norovirus infection and CDI 2. Any apparent correlation in the occurrence of both infections is likely to be attributable to the likelihood of increased ascertainment of CDI during the winter months through a rise in the incidence of viral gastrointestinal infections such as norovirus or rotavirus. This increase in patients with diarrhoeal symptoms during winter can lead to more testing and a subsequent rise in false-positive CDI results 3. Figure 9.6 shows these seasonal peaks in norovirus and CDI occurrence, though it is a lot weaker with regard to the latter.

Another possible explanation for the seasonality in CDI is the impact of increased antibiotic usage in treating secondary bacterial infections following increased admission of elderly patients during the winter months from respiratory infections 3.

However, Figure 9.8 paints a somewhat contradictory picture and appears to show that the observed increase in stool specimens being examined in the winter and the corresponding rise in C. difficile toxin tests does not translate to a similar rise in the proportion of cases that test positive for CDI. There may be a number of reasons for this including variability in the sensitivity of laboratory tests and kits being used across the region.

Figure 9.6: Quarterly laboratory reports of noroviruses and CDI

|

Figure 9.7: Quarterly number of stool specimens examined, C. difficile toxin tests done and the per cent of the latter that are positive for CDI (West Midlands)

|

9.6 Health Economy Approach

Due to the national and regional prioritisation of HCAI prevention and control, and subsequent improvements to CDI surveillance and infection control procedures, considerable progress has been made in reducing the rates of CDI across the region.

To ensure the maintenance of this downward trend in CDI incidence, a health economy-based approach is necessary given our understanding of the interconnections between health and social care provision in acute and community settings. There is a recognition that such an approach requires multi-disciplinary, cross-agency input to identify and tackle local issues that promote the spread of CDIs and to this end, steps have been taken in the region to engage all relevant stakeholders in developing, implementing and monitoring plans to prevent and control CDIs.

Current health economy initiatives of relevance to CDI prevention and control include joint root cause analyses between the acute trust and primary care; cross sector collaboration in promoting the judicious prescribing of antibiotics; and the provision of tools and support to nursing and residential care homes. There are also other initiatives, led jointly by the HPA and Strategic Health Authority, aimed at improving the local and regional surveillance of health-care associated infections, including CDI, through the development new tools, optimisation of existing systems, and provision of training and education to key personnel.

Appendix

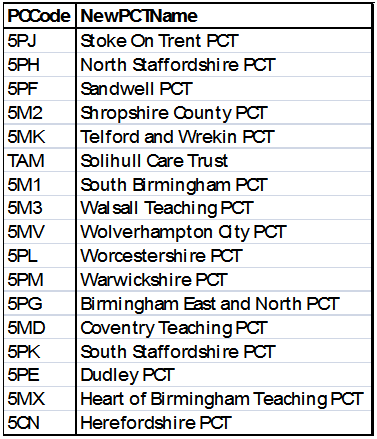

Key to Primary Care Trust codes:

|

References:

- See www.hpa.org.uk/Topics/InfectiousDiseases/InfectionsAZ/ClostridiumDifficile

- See Letter to the Editor: Increased detection of Clostridium difficile during a norovirus outbreak by S.P. Barrett, A.H. Holmes, W.A. Newsholme and M. Richards, Journal of Hospital Infection, Volume 66, Issue 4, August 2007, Pages 394-395

- Health Protection Agency. Quarterly Epidemiological Commentary: Mandatory MRSA bacteraemia & Clostridium difficile infection (up to January - March 2010). Available from URL: http://www.hpa.org.uk/web/HPAwebFile/HPAweb_C/1274091661838

Further information and other useful resources

General information and epidemiological data - For general information and epidemiological data about CDI, including monthly reports by hospital:

C. difficile methodology - new minimum standard for CDI, for implementation from April 2011.

www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publichealth/Healthprotection/Healthcareassociatedinfection/Nationalupdates/DH_114862

Clostridium difficile infection: how to deal with the problem

www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/DH_093220

Noroviruses – for general information and epidemiological data on noroviruses: www.hpa.org.uk/Topics/InfectiousDiseases/InfectionsAZ/Norovirus

All links checked on 28 June 2010

|